Small white towers spread across a cracked and overgrown parking lot on Chicago’s west side. A flurry of stripes and wings buzz through the air, centralizing inside and around the towers. This is one of the apiaries of the urban beekeeping operation Chicago Honey Co-op. The towers are hives, and within, honeybees are busily transforming nectar and pollen into all-natural, urban-produced honey.

Taking the honeybee outside the rural environment and placing it in urban spaces, like rooftops and parking lots, continues to be a rapidly growing trend. Keeping bees in a city, if done correctly, can benefit a neighborhood as a whole. The process goes like this: the bees feast on flowers in one backyard garden. A quick flight to a neighboring garden, and the bees forage there – effectively cross-pollinating and improving the plant health. It continues this way until the bees return to the hive, every day. Flora thrives. And in turn, the bees thrive as well.

“Urban hives are healthier in some cases than rural hives maintained by commercial beekeepers,” says Christian Riechert, manager of Her Majesty’s Secret Beekeeper, a beekeeping and urban homesteading supply store in San Francisco. “There’s a plentiful amount of diverse pollen and nutrients and nectar spectrums from all these different plants. In a rural environment, it may be harder for those bees to exist because there’s not as plentiful or as diverse of a nectar and pollen flow.”

If the neighbors don’t approve of the neighborhood buzz? Explain that honeybees are mostly harmless and give them a jar of local honey. Although, according to many beekeepers, problems don’t arise. Honeybees are gentle. The disconnect comes from a perception that bees are out to sting at their leisure.

“People just see them as insects with stingers,” Christian says. “They don’t see [the bees]as completely natural pollinators of our ecosystem. When the hives are in place, they fit right in. The bees are off doing their thing, and when they’re not off collecting pollen and nectar, they’re in the hives. Rarely are they ever out causing mischief like hornets or wasps.”

The fact is that most neighbors don’t even know the hives are there. Even hotel guests at the Intercontinental New York Times Square, who hosts a hive of roughly 50,000 bees on the seventh floor rooftop, rarely notice the bees. They’re not an in-your-face type of insect.

“Our bees are very friendly,” says Intercontinental Executive Chef Andrew Rubin. “They’re gentle. They don’t get upset. We poke and prod them. They fly off and come home to the hive and there’s no interaction between bees and the guests.”

Proof of the bee’s docile nature surfaces again and again, with images of smiling beekeepers and children covered in bees. A Chinese bee-wearing contest and a Guinness Book of World Records category for the most pounds of bees worn on the body stand as even more evidence. Michael Thompson, Chicago Honey Co-op’s farm manager, even overcame his fear of bees to show a television crew just how harmless the creatures are.

“We were waiting for a TV film crew one day at the Honey Co-op Farm and one of our big hives decided to swarm right when everyone arrived,” he says. “I had always heard a swarm of honeybees is so gentle that you could put your bare hand inside while it is clustered on a branch. I made the mistake of saying this to the TV producer thinking this would calm down the crew and she asked me if I would do it on camera. Of course I had to try it. No one was hurt and I completely lost my fear of honeybees that day.”

Once the hives are ready, beekeepers take on a tricky process to harvest the honey. The bees must be calmed with smoke so the keepers can lift the frames out of the box hives and sweep the bees away. Then the honeycombs can either be cut from the frames, or the frames are run through a machine to remove the honey and funnel it into jars.

While standard commercialized honey producers strive to maintain a regular flavor, urban beekeepers celebrate the complexities of the look, smell, and taste of their locally produced honey.

“In an urban setting, you’re always going to have poly-floral honey,” Christian says. “In rural settings, you start seeing more mono-floral honeys, like a blackberry honey, a clover honey, orange blossom honey. People are used to tasting and comparing cheeses and wines, but there’s a huge diversity in honey that’s incomparable to wine and cheese because of all the different plants producing all the different nectars and pollens in all the different ratios. You get a taste of the different microclimates and the different neighborhoods of the city. It opens up a whole new world in peoples’ minds.”

Urban beekeeping is not without its challenges. The honey produced can occasionally be deemed unusable. It’s difficult to manage the foraging spots of an urban bee colony. Bees carry whatever they get into to the honey. Last year, beekeepers in France were shocked to find their bees producing honey in blue and green shades. It turned out the bees were foraging on processed waste of candy M&M shells. In 2010, New York beekeepers removed frames from the hives to find a bright red, cough syrup-like substance instead of honey. These bees had snacked on syrup from a nearby maraschino cherry factory.

But that’s not to say only urban beekeepers run into issues. Rural bees are prone to forage on more pesticide and chemical-treated plants, which then flows right into the honey.

On the whole, the honeybee population is declining. Pesticides and colony collapse disorder wreak havoc on hives worldwide, spelling out a slow but serious death to plants. In a lot of areas, lawmakers blacklist beekeeping as harmful and dangerous. Many urban beekeepers hope that the practice will raise awareness and acceptance of the bee population, and eventually bring an end to the perception of bees as pests.

Learn more about three urban honeys and try recommended tea pairings.

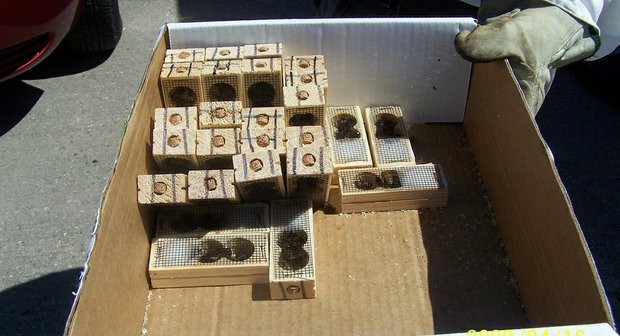

Honey: Chicago Honey Co-op, Chicago, IL

- Foraging Location: Chicago’s west side

- Sight: Milky, pale yellow, thicker than most honey

- Smell: Sweetly bright with a candied flower aroma

- Flavor: A mild flavor similar to commercial honey. The sweetness leaves a slightly bitter aftertaste.

- Pairing: This is a universal honey and would complement any tea well.

- For more information, go to: www.chicagohoneycoop.com

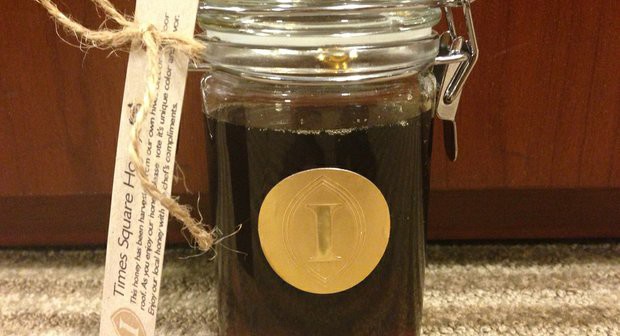

Honey: Intercontinental New York Times Square, Manhattan, New York City

- Foraging Location: Central Park and downtown Manhattan

- Sight: Dark reddish-brown, similar to molasses. Thinner than store-bought honey.

- Smell: Notes of molasses and brown sugar, with the slight scent of a charred whiskey barrel.

- Flavor: A bold smoky cola taste, like dark, almost burnt, caramel

- Pairing: Enjoy a white tea, green tea, or other light tea that allows the honey’s flavor to be the star.

- For more information, go to: www.interconny.com

Honey: Her Majesty’s Secret Beekeepers, San Francisco, CA

- Foraging Location: San Francisco’s central valley

- Sight: This honey in the comb was built right into the container by the bees themselves. The honey itself is a shining golden yellow.

- Smell: Earthy and floral, mildly like a lavender garden.

- Flavor: The flavor betrays the lavender scent with a striking taste of anise, fennel, and rye.

- Pairing: Sweeten a bold tea with this honey, like Lapsang souchong. For a more subdued experience, try with earl grey or mint.

- For more information, go to: www.hmsbeekeeper.com