Moving forward under the sloping eaves of the hundreds-of-years-old wooden entrance gate into the Mampukuji Temple complex, tea aficionados walk into Japanese tea history. Visitors to this Chinese-style temple in the tea-famous region of Uji, Kyoto, discover a world of well-preserved stone and moss gardens, statues of gods, calligraphy, religious paintings, and temple buildings, all designed with the aesthetics of the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). When Chinese Zen Buddhist monk Ingen Zenji founded this temple in 1661, he started a new age in Japanese food and tea culture.

Moving forward under the sloping eaves of the hundreds-of-years-old wooden entrance gate into the Mampukuji Temple complex, tea aficionados walk into Japanese tea history. Visitors to this Chinese-style temple in the tea-famous region of Uji, Kyoto, discover a world of well-preserved stone and moss gardens, statues of gods, calligraphy, religious paintings, and temple buildings, all designed with the aesthetics of the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). When Chinese Zen Buddhist monk Ingen Zenji founded this temple in 1661, he started a new age in Japanese food and tea culture.

Master Ingen not only taught Zen. He also brought bamboo sprouts, watermelon, and kidney beans to Japanese cuisine. Most importantly (for tea drinkers), he introduced a Ming Chinese-style tea-preparation method to Japan. He taught Japanese to steep loose sencha tea leaves. Sencha refers to a type of tea and tea that farmers grow in shaded environments.

To comprehend the impact of Master Ingen and sencha, one must first know how the Japanese concocted and consumed tea before his appearance. Back in the ninth century diplomacy between China and Japan brought new ideas and goods, including pressed tea bricks, to Japan. Nobles and high-ranking monks drank tea for medicinal purposes within the exclusive walls of palaces and temples. However, after a cessation in trade and diplomacy between the two countries, tea drinking almost disappeared within Japan.

To comprehend the impact of Master Ingen and sencha, one must first know how the Japanese concocted and consumed tea before his appearance. Back in the ninth century diplomacy between China and Japan brought new ideas and goods, including pressed tea bricks, to Japan. Nobles and high-ranking monks drank tea for medicinal purposes within the exclusive walls of palaces and temples. However, after a cessation in trade and diplomacy between the two countries, tea drinking almost disappeared within Japan.

A second wave of Japanese-Chinese cultural exchanges in the twelfth century reintroduced tea drinking to Japan. Japanese students of Chinese Buddhism went to China. After Buddhist monk Myoan Eisei returned to Japan, he introduced other Japanese to both Rinzai Zen Buddhism and a Chinese tea ceremony. The ceremony was a Buddhist ritual requiring matcha, powered green tea.

Over the passing centuries, Japanese monks and nobility changed the ceremony. It evolved into a distinct Japanese custom called chado, meaning the way of tea. In the seventeenth century, famous tea master Sen Rikyo formalized the steps and ideals of chado. It became a type of performance art imbued with a philosophy of right living. Rikyo’s teachings still guide chado today. In Rikyo’s time, chado was almost exclusively performed by and for members of the warrior class.

Then, in 1654, Master Ingen Ryuki from China arrived in Japan. He established the Obaku school of Zen Buddhism. Ingen also founded Mampukuji Temple, organized tea gatherings, and introduced the practice of making tea with loose sencha leaves. He used Chinese tea utensils. His tea salons evolved into senchado, meaning the way of steeped tea. In contrast with the warrior class that practiced chado, the first senchando enthusiasts were writers and other artists fascinated by Chinese culture. In lively tea salons, they read Chinese poems and wrote poetry while drinking sencha.

A traveling monk and disciple of Ingen soon paved the way for commoners to enjoy sencha. Baisao—a nickname meaning old tea seller—opposed the formality and exclusivity of formalized tea ceremonies. Tales say that although he had developed a reputation as a tea master, he served sencha to passersby in return for donations. Before he passed away, iconoclastic Baisao reportedly burned his tea utensils as a repudiation of the tradition of revering the tea implements of masters. Wealthy collectors paid inordinate amounts of money for tea bowls and other tea utensils previously owned by famous individuals.

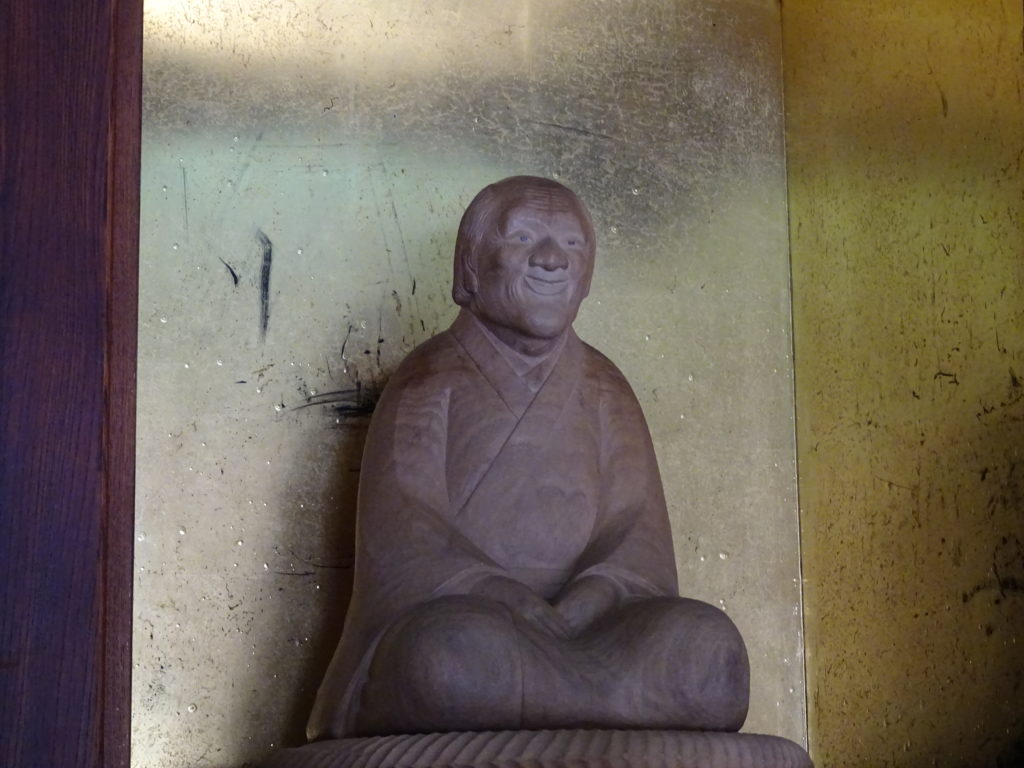

Today, the All Japan Senchado Association has its headquarters within the Mampukuji Temple complex. Machide Tomokazu, the association’s executive director, showed me a statue of Baisao. In contrast to the stern expressions on the faces of most statues of Japanese religious figures, Baisao’s image depicts a relaxed man with a beaming smile. I bowed, wished his spirit well, and then strolled with Tomokazu through a quiet Japanese tea garden just behind a traditional teahouse.

Today, the All Japan Senchado Association has its headquarters within the Mampukuji Temple complex. Machide Tomokazu, the association’s executive director, showed me a statue of Baisao. In contrast to the stern expressions on the faces of most statues of Japanese religious figures, Baisao’s image depicts a relaxed man with a beaming smile. I bowed, wished his spirit well, and then strolled with Tomokazu through a quiet Japanese tea garden just behind a traditional teahouse.

We entered through the back doors midway through a ceremony, but the tea host and guests warmly encouraged my taking photographs. The senchado teahouse was similar to a chado teahouse. The traditional tatami-floored wooden building was decorated with a scroll and seasonal flowers in an alcove. Windows opened onto a view of the carefully swept garden where larges stones sat like sculptured works of art.

We entered through the back doors midway through a ceremony, but the tea host and guests warmly encouraged my taking photographs. The senchado teahouse was similar to a chado teahouse. The traditional tatami-floored wooden building was decorated with a scroll and seasonal flowers in an alcove. Windows opened onto a view of the carefully swept garden where larges stones sat like sculptured works of art.

I noticed narrow cylinder-shaped handle-less teacups in front of each guest. Chado requires open tea bowls because chado hosts need space to whisk matcha powder and hot water into a frothy beverage. Senchado hosts pour from a teapot into cups. In most chado ceremonies today, the guests drink one large cup of tea only. In sencha ceremonies, tea hosts often intermittently refill the cups with tea they have brewed at different temperatures.

I noticed narrow cylinder-shaped handle-less teacups in front of each guest. Chado requires open tea bowls because chado hosts need space to whisk matcha powder and hot water into a frothy beverage. Senchado hosts pour from a teapot into cups. In most chado ceremonies today, the guests drink one large cup of tea only. In sencha ceremonies, tea hosts often intermittently refill the cups with tea they have brewed at different temperatures.

Tomokazu explained that senchado and chado differ in numerous ways. The most noticeable difference is that the chado ceremony requires matcha. Senchado hosts usually serve sencha; however, depending upon their mood, they might prepare gyokuro, hojicha, bancha, or even kocha (black tea). Furthermore, chado is an artistic ceremony in which the tea maker and guests follow scripted rules for making tea, serving tea, receiving tea, and socializing. Modern sencha ceremonies, on the other hand, are flexible, even improvisational gatherings. Many Japanese think that chado has a higher social status than senchado.

Tomokazu explained that senchado and chado differ in numerous ways. The most noticeable difference is that the chado ceremony requires matcha. Senchado hosts usually serve sencha; however, depending upon their mood, they might prepare gyokuro, hojicha, bancha, or even kocha (black tea). Furthermore, chado is an artistic ceremony in which the tea maker and guests follow scripted rules for making tea, serving tea, receiving tea, and socializing. Modern sencha ceremonies, on the other hand, are flexible, even improvisational gatherings. Many Japanese think that chado has a higher social status than senchado.

Interaction between guests and hosts also distinguishes the two arts. Chado, Tomokazu explained, is based on four elements: harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility. During chado ceremonies, the conversation is often restricted to themes such as tea utensils, decorative scrolls, flowers, and, of course, tea. A contemplative silent appreciation of the tea taste, tea room, and the surroundings are part of the practice. Senchado includes the first three elements, but tranquility is less emphasized. Senchado allows for passionate social exchanges. Senchado hosts encourage laughter and lively conversations on numerous topics.

Interaction between guests and hosts also distinguishes the two arts. Chado, Tomokazu explained, is based on four elements: harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility. During chado ceremonies, the conversation is often restricted to themes such as tea utensils, decorative scrolls, flowers, and, of course, tea. A contemplative silent appreciation of the tea taste, tea room, and the surroundings are part of the practice. Senchado includes the first three elements, but tranquility is less emphasized. Senchado allows for passionate social exchanges. Senchado hosts encourage laughter and lively conversations on numerous topics.

In conclusion, Senchado and Chado are both Japan-specific arts based on tea appreciation. Neither is better than the other. The Uji region of Japan is renowned for its teas and its tea history. Mampokuji Temple is within Uji. If you are a tea lover who wants to experience the history and savor the taste of Japanese tea, Uji is the place to visit.

Greg Goodmacher

Greg Goodmacher

Exploring multicultural perspectives of all things brings zest to his life. Greg has savored various teas in over twenty countries on four continents. Greg teaches cultural and global issues at a college in Shibata, Japan. He takes green tea to classes, mountain peaks, and hot springs. In addition to studying, enjoying, and writing articles about tea and Japan, Greg also blogs about Japanese hot springs.