High up in the Himalayas, yaks roam the Tibetan countryside. Chilled winds whip across the landscape as a farmer milks his herd. The milk will soon get churned into thick butter, but not for eating. While yak butter is used in many parts of the Tibetan diet, this butter’s destination is a cup of tea.

Yak in Time

In Tibet, drinking yak butter tea, or po cha, is a centuries-old cultural tradition. It’s available at restaurants and in homes, and Tibetans drink it throughout the day, morning, afternoon, and evening. The group has been known to individually drink up to forty cups per day. In fact, po cha is so prevalent that there’s even a special food to go along with it. TsampaI, made from roasted barley flour, is more or less a biscuit, which is dipped into the tea.

To really understand why yak butter tea is so dominant in Tibetan life, it’s important to know a bit about the lifestyle and climate up in the Himalayas. High altitudes bring with them exhaustion and food scarcity. For a farmer, both energy and calories are necessary to get through the day—and po cha provides both of those on a steaming, buttery platter. Butter in the tea helps the calorie count to skyrocket, and a higher caloric intake often translates into more energy. But that’s not the only health benefit. It is tea, after all, and comes with the same unique perks of any cup: vitamins, digestive health, cardiovascular benefits, and sharper concentration.

To really understand why yak butter tea is so dominant in Tibetan life, it’s important to know a bit about the lifestyle and climate up in the Himalayas. High altitudes bring with them exhaustion and food scarcity. For a farmer, both energy and calories are necessary to get through the day—and po cha provides both of those on a steaming, buttery platter. Butter in the tea helps the calorie count to skyrocket, and a higher caloric intake often translates into more energy. But that’s not the only health benefit. It is tea, after all, and comes with the same unique perks of any cup: vitamins, digestive health, cardiovascular benefits, and sharper concentration.

The Traditional Cup

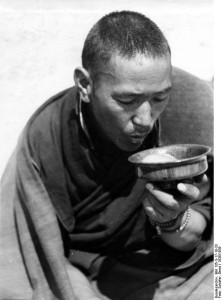

Making traditional po cha requires a good deal of patience. Tibetans use compressed bricks of either pu-erh or black tea to make a tea base, a concoction called chaku. Leaves crumbled from the pu-erh brick are boiled for anywhere from a few hours to several days until the tea is black, bitter, and smoky. From there, the chaku is poured into a tall wooden churn with the yak butter and salt, churned until all the lumps are gone, then served warm in a shallow bowl. The result is a creamy, bitter, and slightly salty mixture that’s more like a broth than a tea. Oils from the butter leave an almost waxy coating on the drinkers’ lips and mouths—Tibetans will often drink this as a stand-in for lip balm, another benefit of the tea for mountainous living.

Making traditional po cha requires a good deal of patience. Tibetans use compressed bricks of either pu-erh or black tea to make a tea base, a concoction called chaku. Leaves crumbled from the pu-erh brick are boiled for anywhere from a few hours to several days until the tea is black, bitter, and smoky. From there, the chaku is poured into a tall wooden churn with the yak butter and salt, churned until all the lumps are gone, then served warm in a shallow bowl. The result is a creamy, bitter, and slightly salty mixture that’s more like a broth than a tea. Oils from the butter leave an almost waxy coating on the drinkers’ lips and mouths—Tibetans will often drink this as a stand-in for lip balm, another benefit of the tea for mountainous living.

If you happen to end up in a Tibetan home with a bowl of po cha in front of you, remember that even if you don’t like the taste, you must be polite. Take at least a sip. Customarily, your bowl will never be empty—your host will refill it to the brim after each swallow. If you hate it and don’t want to drink it, etiquette is to leave it alone. Once you’ve left, the person serving will dispose of your leftovers, and you’ll have avoided that embarrassing cultural “oops” of offending your host accidentally.

A Brew for You

Want to try it yourself but don’t have the means to get to Tibet? You’re in luck—we have a recipe! We made a few edits for ingredients more accessible in the United States. But if you somehow manage to get some yak butter and pungent brick tea, give it a try and let us know how the taste changes.Tibetan Yak Butter Tea (Po Cha)

Ingredients:

4 cups water

4 teaspoons loose lapsang souchong

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1/2 cup milk (optional)

Instructions:

Boil the tea in the water for 5 minutes.

Strain and return to heat.

Stir in salt.

Add the butter and whisk or blend until frothy and smooth.

Pour the mixture into a shallow bowl or small cup.

Add milk to sweeten, if desired.

Serve hot.

You can substitute any strong, black tea for the lapsang souchong. In Tibet, the tea comes from a Pu-erh brick. Any unsalted butter will work as well. Let us know how it turns out!