If Pu-erh tea were a child, she would be difficult, brilliant, and misunderstood

. Perhaps no other tea elicits such passion: Devotees herald its unique taste, its fabled history and its health benefits, while detractors say it tastes like mud and looks like dirt. Pu-erh tea was even once banned from entering the US.

“Chinese herbalists have been prescribing it for thousands of years,” says legendary tea pioneer and pu-erh expert Roy Fong, owner of the Imperial Tea Court in San Francisco and Berkeley. “We know that it helps with digestion. And there’s a very good reason for that: If you put hot water to grease, you will start to dissolve the grease. Hot pu-erh tea dissolves grease even better and makes the system work better.” Another reason, says Fong, is that well-aged pu-erh is easier to drink in large quantities than a more astringent tea. “It’s just the nature of shou pu-erh: it’s milder and gentler.” And the bacteria growth that comes from the fermentation process is “almost like a probiotic.”

[groups_member group=”Paid Subscribers”]“Pu-erh teas are infamous in this country because the Chinese treat them so that they produce a mustiness,” said Robert Dick, once the chief tea examiner of the US. “To the tea expert in this country, mustiness is something on which they all agree: they would throw it out.”

Not so fast. Despite Dick’s admonition, tins of “Chinese Tea,” were widely available then and now. Misao Cooper, a manager of Spruce Restaurant in San Francisco, recalls eating upscale dim sum in Guangdong and drinking some delicious tea. When he asked if he could buy it for friends back home, he was given none other than the ubiquitous tin.

“It’s my daily beverage of choice,” say Ned Hegearty, owner of Silk Road Tea in Northern California. “I don’t feel caffeinated; I feel more central body warming.”

Pu-erh tea has been heralded in controlling weight, lowering high blood pressure, and even shrinking tumors. Media star Dr. Mehmet Oz recently touted its weight-loss virtues on national television, prompting what teashop owner Sally Collura calls “The Dr. Oz effect.” Says Collura, proprietress of Tea Leaf in Waltham, Massachusetts. “My phone rang off the hook. But I told my customers that it’s not a magic drink that will help them lose 50 pounds; they need to think about what they’re eating.”

For years, scientific journals in Asia and Europe have featured studies on pu-erh, but there’s not much data in the US. In a 2004 review of flavonoids in green, black and pu-erh, Tufts University scientists noted that “analytic data for (oolong) and pu-ers on catechins were sparse and more data are needed.” (1)At the 5th International Scientific Symposium in Washington this past September, the only mention of pu-erh came from an audience query by Canadian nutritionist and tea expert Michelle Hamilton.

So what is known? One of the most intriguing studies comes from China on the role of pu-erh in metabolic syndrome. Affecting an estimated 25% of Americans, it’s characterized by big bellies, elevated blood sugar, abnormal cholesterol and high blood pressure and can lead to type 2 diabetes, stroke and heart disease. In the Chinese study, 90 patients with metabolic syndrome were either given pu-erh or a placebo. After 3 months, the pu-erh group had significant improvements in their HDL, glucose and amount of belly fat. (2)

Another 2011 study from Japan gave overweight men and women either powdered pu-erh mixed with barley or just barley tea. After 12 weeks, the pu-erh group lost significantly more weight and had less belly fat than the placebo group who only drank barley tea. “This is the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that revealed reducing effects of BTE (black tea extract of pu-erh) on mean BMI (body mass index) and body weight values in overweight Japanese subjects,” wrote the researchers.(3) Previous studies had demonstrated the effect of pu-erh on animals, such as the one at Yunnan Agricultural University. Scientists fed rats high fat or normal diets. The fat rats who were given pu-erh tea extracts had significant reduced body weight compared to the control rats. (4)

One factor is gallic acid, a natural anti-oxidant that is also an anti-fungal, antiviral, and anti-obesity agent. The fermentation process of pu-erh elevates the levels of gallic acid, while reducing catechins. In a 2001 study, scientists at University of Massachusetts and University of Michigan found that pu-erh had twice the amount of gallic acid than black tea and four times that of green. (Conversely, pu-erh has a third of the amount of catechins found in green tea.) (5)

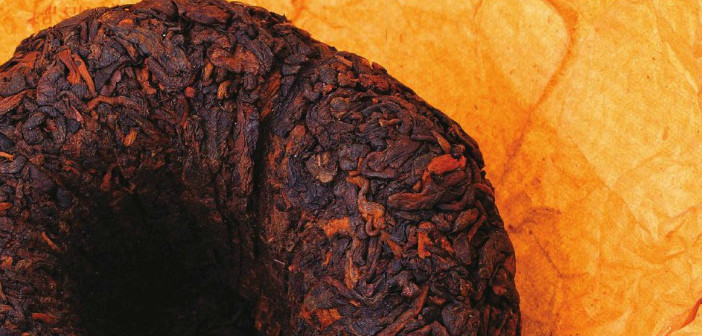

The history of pu-erh is as tantalizing as the health benefits swirling around it. Since the Tang Dynasty, the tea was harvested in Yunnan Province from forest trees of the Six Famous Tea Mountains. The tea was processed, sun-dried, packed into bamboo baskets and transported to areas near the central city of Pu-erh where it was rehydrated, steamed, compressed into bricks, and put on pack animals for the long journey to Tibet and beyond. During the Song Dynasty, pu-erh – which developed a mellow, aged taste during transport– was exchanged for horses; hence the name Tea Horse Road. It soon became known for its medicinal properties as well as taste. Because aging took so long – sometimes ten to 30 years – Chinese scientists in the 1950s found a faster way to age the tea with a similar result. The result was “shou” — cooked or fermented tea –as contrast to “sheng” the raw tea aged for years. Today, pu-erhs come from other provinces in China and Vietnam, but in 2003, the Chinese government degreed that authentic pu-erh can only come from Yunnan. In contrast, modern methods can produce faster results, but may not achieve the same depth of flavor or potential value. This can make a significant difference, especially for collectors willing to pay a premium for traditionally aged Pu-erh, which can cost upwards of a 1000 dollar loan for a single cake.

In the final sip, pu-erh remains alluring and simply delicious, regardless of health claims, “ “It’s like believing in God,” says Roy Fong. “If you are a religious person, you think God is responsible for everything. But if you are somewhat religious and you have common sense, you know you have to do your part too.”

[/groups_member] [groups_non_member group=”Paid Subscribers”]Want to read more?

You need a subscription to view the full article – click here to subscribe!

[/groups_non_member]