The following piece is the second of three installments that sheds light on the production of Yerba Mate and its cultural and economic impacts of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay by Klas Lundstrom. You can catch up on part one here.

*This piece contains some strong language. In an effort not to censor the people interviewed, or offend the reader we have kept the words but altered some letters with a dash (-). *

Tareferos (leaf pickers) and ADT union activists get together for a Saturday barbeque, offering pastries and soda, while the rain pounds the tin roof. There are also reviros, a typical tarefero dish made of flour and fat. The dish’s origin is said to spring out of poverty; legend has it that a mother was grieving the fact that she didn’t have the means to provide for her children. As she wept over a pot of flour, her tears provided enough moisture to make a dough out of the flour.

Daniel Rodriguéz recalls the reviro plate he had on the morning October 2, 2000, in Colonia Aurora, along the Brazilian border. It was his last meal before everything went to hell. After the meal, Daniel filled his second sack with maté leaves for the day and set off for the awaiting truck at the end of the clearing.

“But there, waiting, was another truck,” he remembers. “Not the one we usually drove to the mill with. This one was a real piece of s—. But what could we do? We just loaded the f—– and hopped on top of it. It’s not the tarefero’s job to ask questions.”

Off they went, and down the roadside.

Daniel retells the ordeal with vivid details and a self-empathy learned after many years of recurring nightmares. His body was broken, and the accident was followed by five years of rehabilitation – and unemployment. He couldn’t walk for a long time, and his fear of riding trucks convinced him to seek assistance from the provincial authorities.

“I was treated as if I were a criminal,” he says. “The maté company wouldn’t help me, as far as they’re concerned, there were no papers linking me to them. And in the eyes of the authorities, during a national economic crisis, I was a todo negro, someone who’s not entitled to unemployment assistance, so there was no chance in hell for me to get counseling, compensation, nada. My family and I were hung out to dry.”

He can understand why his then-girlfriend broke up with him and took their child with her into another relationship. One where there were better possibilities for putting food on the table.

“She didn’t think I would be able to walk again or work,” he says. “I was left to recuperate alone. And once I was physically healed, to keep on working as a tarafero was the only option I had. I just pray for my child to stay at school.”

Broken bones may heal, but the scars after a broken life remain. As a child, he dreamt of a career as a soccer player.

Now, as a man in his mid-40s, Daniel has limited mobility due to his accident. As he looks back, he reflects that things couldn’t have happened in any other way; the life of a tarefero is bound to social and economic structures, rooted in the region’s historical DNA.

“I was 26 years old at the time of the accident,” he says, “Now, I fear every truck transport. I have no choice, if I don’t go, I won’t get paid – but it’s a fear that never leaves my body.”

Out there, in the woods and remnants of a once staggering wilderness, are whole families living in shelters of tarpaulins and cardboard – a parallel society whose inhabitants enjoy no access to healthcare, education, or proper housing.

“They live their lives as modern slaves,” says Roque Pereira.

Tarefero camps, where minors and small children live out in the wild under horrific conditions, reach the local press in the wake of dismantling raids. “But these people’s fates, and why they are forced to live out there in the first place, seldom reach the public’s eye. And these findings are only the tip of an iceberg. There are many people out there.”

There are no reliable numbers, but it’s estimated that tareferos and their families number 75,000 people in Misiones alone. Roque credits the lack of reliable numbers to political and economic interests that depend on the status quo.

“The whole industry is dependent on poor people to take on the most dangerous and least paid jobs,” he says.

One new settlement of maté workers has popped up in the outskirts of Oberá, in a valley next to a middle-class suburb. This working-class barrio, called Sapucay, is made up of shacks built with damaged wood and tin. There is limited access to running water, and the only electricity is produced by generators or stolen from nearby power lines. Dogs keep watch in sliding mud. Basic needs are ignored by authorities; fatal flooding has occurred, children are living without proper necessities, and many teenagers have already fallen into addiction.

The barrio is emptied during the day; most families are taking day jobs on maté plantations. A resident of the middle-class suburb next door, whose brick house sits behind a security fence, regards the inhabitants of Sapucay as “friendly ghosts,” like creations of a parallel reality.

“These people live completely beside the rest of society,” says Patricia Ocampo, co-founder of Un Sueño para Misiones (“A Dream for Misiones”), an organization that tackles child labor within the maté industry. “Misiones’s indigenous people are forced to take the least paid and most dangerous jobs.”

She points down the valley, but might as well refer to all of Misiones: “Now, they occupy land that used to be their ancestors’ home.”

* * *

On a road that cuts through the Núñez family’s outstretched, century-old maté plantation, a lonesome ant carries the remains of a leaf. Now and then the ant stops, as if catching its breath, before amending the burden and then continuing its trek to the other side of the road.

Ana María Núñez, the current farmer and steward of the Santa Inés plantation, knows this place by memory and love. She has wandered here her whole life, upon Misiones’s mineral-rich red soil, and she never gets tired of the land. She loves the interplay between nature and its inhabitants, and the untouched jungle pockets surrounding maté plantations.

“Jungle was all you found here until the first decades of the twentieth century,” Ana María explains. “Back then, in the early days, there were no roads or means of transportation, so all the harvest had to be dragged and carried through the jungle, and down to the river.”

The river, Paraná, is still there, separating Argentina and Paraguay. The plantation still holds a sense of ecological purity and social isolation, despite the proximity to the city of Posadas. At dawn, the world springs to life with the roars of brown howler monkeys, rather than traffic from Road 105.

“I’m glad that neither my grandfather nor the generation of my parents cut down this land,” she says. “All has been allowed to live on, thus making a walk here like a stroll back in time.”

The sense of timelessness is embodied not only in Santa Inés’s architecture, but in the sense that this is still a frontier; geographically isolated and far away from national capitals, and economically dependent on the earth.

Four centuries have passed since the first Jesuit missionaries set up camps, known as “Reductions,” to convert the semi-nomadic Guaraní tribes. For much of that time, the Atlantic Forest remained a hostile and impenetrable environment. But from the turn of the twentieth century, things have changed rapidly.

“People came here in search of maté trees,” says Ana María. “To them, maté was the path leading to a better life. It was their green gold.”

Organizing maté production in Misiones, however, turned out to be a difficult task. Maté trees grow wild and free all over Misiones, as well as in southern Brazil, Paraguay, and even in some parts of Uruguay. Still, farmers found it difficult to grow maté on fields, outside the jungle. Although missionaries learned the secrets of cultivating the plant in the countryside from their newly converted Guaraní brothers and sisters, it was a secret they never passed on. Then, in the early 1900s, a band of immigrant adventurers and entrepreneurs spent large sums of money and time to tame the herb that thousands, if not millions, of people – from Buenos Aires’s upper-class to the workers in Chilean copper mines – consumed daily.

“One of them was my grandfather,” says Ana María.

Pedro Núñez migrated from Spain to Buenos Aires in the 1870s before settling down in Posadas, then the gateway to Misiones’s maté bonanza. In 1901, Pedro Núñez became the first tourist entrepreneur to organize a river voyage to the mighty waterfalls of Iguazú, shortly prior his purchase of the piece of land that was named after his mother – Inés. Like many others, explains his granddaughter Ana María, he took a gamble and desperately tried to accustom the maté seeds to the red soil.

“But they couldn’t pull it off, and no one understood what they did wrong; they had the seeds, the climate, and the tools to make it happen – but the trees just wouldn’t grow.”

It wasn’t until the maté farmers let the seeds pass through the digestive system of birds that they started to grow, and when the trees began to pop up, the forest made way for plantations. The plantations then paved the way for an industry whose importance to the producing countries’ economy – and national identity – cannot be underestimated.

“To me, as a maté farmer, above all, it’s a way of life,” says Ana María.

She leads the way through hidden jungle pockets and fields. She halts, points at changes in the soil, or embraces trunks and whispers to them. In the background, the noise of tractors and chainsaws shred the silence. Days of harvesting are busy and noisy. For the Núñez family, the autumn harvest marks the end of a waiting game with Mother Nature.

“It takes time and patience to have maté trees grow without the use of chemicals and pesticides,” she says. “If you choose to cultivate maté in a sustainable way, one must look after the soil and let nature do her job. Now, we can enjoy the harvest and make way for the beginning of the next crop cycle.”

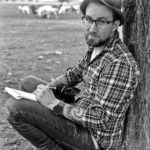

Photos were taken and kindly provided by the author, Klas Lundstrom.

About the author: Klas Lundstrom (b. 1982) is a self-taught writer and journalist based in Stockholm, Sweden. He started writing as an eleven-year-old trying to cope with the death of his father. Author of numerous nonfiction books on, e.g., the U.S. uranium industry and its social and environmental impacts, Latin America’s forgotten regions, and East Timor’s walk from Indonesian occupation to U.N. colony. As a reporter, he has contributed numerous media outlets throughout the years, e.g. The Guardian, The Jakarta Post, and TT, Sweden’s equivalent to Associated Press. He has lived in both Brazil and Uruguay and is a dedicated yerba maté consumer and hopes that his reporting on the maté industry can help other consumers understanding the business, and thus make more ethical and aware choices regarding products, companies, and origin.

Learn more about Klas Lundstrom, and follow him on Twitter.