The History of Jo-an Teahouse

A tea garden named Urakuen is to the world of Japanese tea what the Louvre Museum is to European art, and a small teahouse within Urakuen is what the Mona Lisa is to the Louvre.

Named after Tea Master Oda Uraku, the garden preserves the quietude of tea culture in the center of frenetic modern Japan. Priceless centuries-old buildings and stone artworks are integral parts of the garden. The tiny seventeenth-century teahouse called Jo-an draws visitors from around the world. It’s one of the roots that nourish the tea ceremony of today.

Jo-an is a much-traveled building whose wooden, earthen, and bamboo walls speak of hundreds of years of Japanese history. The Japanese government designated the hut-like, 12-by-12 foot building as a national treasure in 1936. In 1618, Oda Uraku (1548-1622) ordered the construction of Jo-an on the grounds of Shodenin Temple in Kyoto.

Uraku was first a powerful Japanese daimyo, or feudal lord, and then a tea master and monk. Uraku was also a devoted disciple of Sen no Rikyju, (1522-1591) the man whom the Japanese venerate as the greatest teacher of chado, or the “way of tea.”

Swept along by time and economic, political, and societal changes, Jo-an was moved 226 miles to Tokyo on carts—carefully pulled by humans, not horses. The head of the Mitsui family (past owners of the Mitsui Company), Takamine Mitsui, purchased Jo-an. In 1908, he brought it to his family residence, where elite members of Japanese society held ceremonies in the teahouse until American bombers began attacking Tokyo in the nineteen forties.

To protect it from extensive firebombing by the American military, the Mitsui Company moved Jo-an from Tokyo to Kanazawa. The fragile building was disassembled and the pieces were moved by, ironically, Ford trucks, which were reportedly the largest and the best trucks in Japan at that time. In the back of each truck sat a carpenter who held wooden beams, bamboo poles, and other sections of the building between their legs or on their laps to safeguard them during the rocky ride.

The convoy of trucks bearing the teahouse was escorted by a phalanx of police. Part of the route was on national freeways, but to protect the irreplaceable contents, the trucks drove twenty miles an hour. Because the trucks were wider than some of the rural roads on the route, the Mitsui Company purchased roadside properties, demolished homes, and built a wider bridge over a river.

Transporting Jo-an to the countryside turned out to be a perceptive move; the primary Mitsui residence was destroyed by Allied bombs, but Jo-an was safe on the Mitsui family’s vacation property for approximately thirty years. In 1972, the Nagoya Railroad company purchased Jo-an from the Mitusi Company and put the teahouse inside Urakuen.

When Jo-an was brought to Urakuen, two famous teahouses were reunited. After retiring from the exalted position of daimyo, Uraku lived in a temple named Shodenin, where Uraku had originally built Jo-an.

He had also designed another building, called Shodenin Shoin, to serve as his home, study, and teahouse for large gatherings. It’s a simple structure with tatami floors and a wooden veranda under a tiled roof. The original Shodenin Shoin was destroyed long ago, but artisans recreated an identical building from Oda Uraku’s original construction plans.

Today, visitors can drink matcha on the veranda of Shodenin Shoin. While sipping from a bowl of freshly-stirred, aromatic green tea, you can contemplate life and a Zen-inspired garden, like Uraku did about four centuries earlier.

Strolling through Urakuen

The phrase “Japanese garden” covers a wide variety of garden genres: Zen gardens, sacred gardens, rock gardens, tea gardens, and others. Tea gardens are designed for strolling and contemplating the vistas within. Squiggly paths of irregular stones and the beauty of the garden make visitors walk slower than usual.

Urakuen’s size is just over three acres, but the skillful use of a Japanese landscaping technique, miegakure, makes it feel much larger. The Art of the Japanese Garden explains that miegakure means “hide and reveal.” Meandering paths lead visitors’ eyes to one gorgeous vista, such as a sunlit mossy plot with Japanese maple trees and stone lanterns, while a few yards away another landscape is blocked by a hedge, large stones, or fences.

Walk around the hedge. A new scene is revealed. You have entered a silent and cool grove where tall, thin, stalks of multihued-green bamboo plants, waving in the wind, filter the sun’s rays. It feels like a separate world. Following one of several windy stone paths from there could bring you to a different landscape with an invaluable work of art set amidst carefully arranged stones, flowers, or shrubs.

One small path led me to the view of an elegant, but primitive-looking, hollowed-stone water basin. Hidden beneath it was an extremely rare underground water zither, called in Japanese, suikinkutsu. A vertical bamboo pole jutted from the ground. From a thinner cantilevered piece of bamboo, a clear thin stream of water poured into the hewn stone basin, creating the sound of a small stream.

One small path led me to the view of an elegant, but primitive-looking, hollowed-stone water basin. Hidden beneath it was an extremely rare underground water zither, called in Japanese, suikinkutsu. A vertical bamboo pole jutted from the ground. From a thinner cantilevered piece of bamboo, a clear thin stream of water poured into the hewn stone basin, creating the sound of a small stream.

Suddenly I heard the high pings of a ceramic bell, but where was the bell? Water from the overfilled basin was sliding over one side of the stone basin into a gravel-filled depression in the soil. I later learned that an upside-down ceramic pot was buried beneath the gravel. Drops of water, finding their way through a hole in the gravel-covered pot, were falling into a small pool of water under the pot and the surrounding gravel. Each falling drop causes a splash that rings upward, reverberating like a bell.

Within Urakuen, Miegakure also conceals Jo-an in a secluded inner garden. Jo-an is written with two Japanese kanjis (如 and 庵), which mean “the ultimate meaning of all things”, and “hermitage”. Entering its grounds feels like entering a sacred retreat.

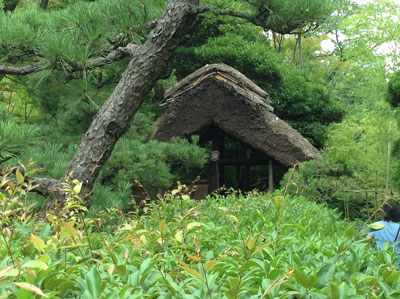

Impenetrable hedges, over two meters high, guard the secret garden and its antiquities. The entryway is through a narrow Kayamon Gate. One approaches the gate from the side. Pressed tightly on each side by thick hedges, it looks like a minuscule rustic hut in a mountainous region. The gate is constructed of dark brown wooden poles and covered with a dark thatch roof. I mistook it for the famous teahouse until I came closer.

Impenetrable hedges, over two meters high, guard the secret garden and its antiquities. The entryway is through a narrow Kayamon Gate. One approaches the gate from the side. Pressed tightly on each side by thick hedges, it looks like a minuscule rustic hut in a mountainous region. The gate is constructed of dark brown wooden poles and covered with a dark thatch roof. I mistook it for the famous teahouse until I came closer.

The low thatch roof makes one bend forward, so your eyes look downward. Straighten up, and the centuries-old teahouses appear. A stone walkway leads toward them but pauses first at a large flat rock where the lane splits into smaller paths. The left path leads to an oval stone basin that was used for purification before tea ceremonies. It was designed to be low to the ground so that visitors, regardless of rank, stoop when ladling water for washing their mouths and hands. The message is to be humble.

The next stop is Jo-an. Visitors can stand next to it and peer through the open windows at artistic touches that influence Japanese art today. Oda Uraku’s creative ideas also contributed to Jo-an’s fame. He covered a section of one wall with ancient lunar calendars. Another famous design is a round window latticed with interwoven vines. These were all new features.

Over the last several hundred years, architects and teahouse designers have been copying or integrating designs from Jo-an into their own plans. Jo-an represented an ideal teahouse in its environment, and it became an archetype throughout all Japan for the “small-hut style” of teahouse.

Although, Jo-an is too precious for public admission, a select group of tea masters, for a limited number of special occasions, may enter Jo-an to perform tea ceremonies. Even though you cannot enter Jo-an, its historic atmosphere seems palpable.

The Urakuen garden is many things: a time capsule, a museum of teahouses, a sensual experience, and an introduction to Zen history that is, naturally, best experienced with a Japanese bowl of matcha. The inspiring aftertaste remains long after strolling out the gates of Urakuen.