note that this article was previously published on October 28th, 2014

Leaves shift to deep, golden and amber hues that catch the fading sunsets as pumpkins move from the winding vines within the patch to our doorsteps. Spiced lattes fill cafes and scent out kitchens. Fall is here. Although in the Japanese culture, the fall harvest is celebrated in September and October with Otsukimi, the mid-autumn harvest moon-viewing celebration.

It is customary to celebrate the beauty of nature with Japanese festivals: cherry blossoms in the spring and the moon and autumn-harvest in the fall.

I had the pleasure of attending a moon-viewing tea ceremony in Philadelphia at the Shofuso Japanese House and Garden, where tea was served to us on the covered veranda overlooking the garden as twilight gave way to dark night sky.

Introduced by China in the Nara period (710-794), Otsukimi has been a part of the Japanese culture since the Heian era (794-1185). Traditionally, Japanese aristocratic families would host moon-viewing events aboard boats, as to see the reflection of the moon on the surface of the water.

An offering table is still lined with bowls featuring seasonal crops (chestnuts, persimmons, taro), plants and round rice dumplings (known as dango), as an offering to autumn’s full moon in hopes of a plentiful harvest. During such a celebration it was common to host a moon-viewing tea ceremony whether on a boat, out amongst nature or in a tea house.

Sweet rice dumplings, dango, are similar to the familiar mochi (which Americans know as being filled with ice cream). The rice dumplings are paired with matcha green tea and served during the tea ceremony. Dango is often made with a rice flour exterior and filled with a range of ingredients, such as sweetened red bean paste, eggs, chestnut paste, etc. There are even green tea flavored Dango, referred to as Chadango (“cha” translating to “tea”).

Sweet rice dumplings, dango, are similar to the familiar mochi (which Americans know as being filled with ice cream). The rice dumplings are paired with matcha green tea and served during the tea ceremony. Dango is often made with a rice flour exterior and filled with a range of ingredients, such as sweetened red bean paste, eggs, chestnut paste, etc. There are even green tea flavored Dango, referred to as Chadango (“cha” translating to “tea”).

While Americans see the faces of the man in the moon, Japanese folklore notes seeing a rabbit pounding rice flour in a mortar and pestle to make mochi. Inspired by that folklore, Dango is served during the tea ceremony (and also because its round shape and white rice flour coloring give it the appearance of the moon).

The Otsukimi tea ceremony follows Japanese tradition, in that the host prepares a bowl of matcha for each guest in attendance. While there are entire books devoted to the art, culture and tradition of the Japanese tea ceremony, I will share just a glimmer of what I experienced during my first Otsukimi tea ceremony. The ceremony itself reminds me of a ballet; thoughtfully practiced movements are gracefully threaded together. A small set of customary tea utensils dance about ever so quietly to prepare the bowl of matcha green tea.

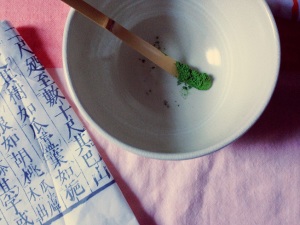

The ceremony begins as the host carefully unpacks the tea utensils, wiping them clean with folded cloths. The tea bowl, chawan, is warmed, rinsed and dried. The matcha green tea is gently tapped from its canister into another small dish. The bamboo chashaku, tea ladle, is dipped into the vibrant green tea powder to measure the perfect bit need for each bowl within the gentle curvature of the scoop. The tea meets the inside the chawan tea bowl.

The ceremony begins as the host carefully unpacks the tea utensils, wiping them clean with folded cloths. The tea bowl, chawan, is warmed, rinsed and dried. The matcha green tea is gently tapped from its canister into another small dish. The bamboo chashaku, tea ladle, is dipped into the vibrant green tea powder to measure the perfect bit need for each bowl within the gentle curvature of the scoop. The tea meets the inside the chawan tea bowl.

Steaming water is poured over the vibrant tea with such  precision that it seems as if a stream appeared above the bowl. The delicate bamboo spokes of the tea whisk, chasen, quickly whip the tea infused water like a rush of wind, until frothy foam covers the surface. These rapid strokes seem to echo that of a cymbal in a grand orchestra performance, noting the final moments before the bowl of tea is carefully handed to the guest.

precision that it seems as if a stream appeared above the bowl. The delicate bamboo spokes of the tea whisk, chasen, quickly whip the tea infused water like a rush of wind, until frothy foam covers the surface. These rapid strokes seem to echo that of a cymbal in a grand orchestra performance, noting the final moments before the bowl of tea is carefully handed to the guest.

There is an emphasis on ways in which the tea bowl is turned  prior to the first sip, and a final slurp that alerts the host that the guest has finished their tea.

prior to the first sip, and a final slurp that alerts the host that the guest has finished their tea.

Tucked within the ceremony is the presentation of a sweet, whether it be a small wagashi treat, mochi or even small dishes of savory bites throughout a lengthier ceremony. Before passing the chawan bowl back to the host, the guest takes the time to observe the details of the bowl, paying respect to the artist’s handcrafted beauty.

The tea utensils are then delicately cleaned, a sign of respect to the guests, and carefully placed back into their box with a great sense of purpose. It’s at this moment you sense that what you’ve experienced is incredibly powerful, yet calming, washing over you with tradition and a refreshed perspective.

The tea utensils are then delicately cleaned, a sign of respect to the guests, and carefully placed back into their box with a great sense of purpose. It’s at this moment you sense that what you’ve experienced is incredibly powerful, yet calming, washing over you with tradition and a refreshed perspective.

While I dance about the details of the ceremony, highlighting the bright moments throughout the steeped journey, I must note that it’s not even possible to describe each graceful second. Letters could not be threaded together to capture the emotions one feels when participating in a ceremony that carries such traditional weight and effortless beauty.

Each element has a quiet power that leads to experiencing a transformative bowl of match tea and creating a deep connection between host and guest. Although the one moment that is truly your own is when the matcha meets your lips. The powdered tencha tea whisked into a smooth cup seems to coat your palate with rich umami flavors that walk the line of creamy and vegetal with a subtle sweet note.

Pleasant bitter flavors are reminiscent of the first bite of a dark chocolate bar, although these grassy notes with a bit of bite are quieted by the wagashi sweet or mochi pairing. Treasuring each drop, I imagined the tencha tea leaves shaded during the last weeks leading up to their April harvest.

I tried to channel the warmth of the freshly picked leaves being steamed and gently dried, having veins and stems removed before being ground into a fine powder in an ancient stone mill.

As the final moments of the moon-viewing festival came to a close, bowing in appreciation for a truly memorable evening, I took a deep breath of the chilled autumn air wafting in from the garden, now completely awash with darkness. The sense of calm was both grounding and exhilarating, connecting me to the nature that we celebrated. It was as if the moon was my bright balloon that I held onto with a string threaded with each bit of matcha tea powder, pulling me to the sky yet keeping me on my feet.

As the final moments of the moon-viewing festival came to a close, bowing in appreciation for a truly memorable evening, I took a deep breath of the chilled autumn air wafting in from the garden, now completely awash with darkness. The sense of calm was both grounding and exhilarating, connecting me to the nature that we celebrated. It was as if the moon was my bright balloon that I held onto with a string threaded with each bit of matcha tea powder, pulling me to the sky yet keeping me on my feet.

Vowing to seek elements of this state of mind, the very next evening I carefully opened a box that housed my Ippodo matcha set. The chawan, chashaku and chasen tucked within with a cloth and tiny jar of matcha found their way to my urban oasis in my small patio garden.

Placing each tea utensil on a coral blanket, I thoughtfully whisked a bowl of matcha under a fall sunset sky watching the golden hour fade into twilight. I cupped the bowl with both hands and buried my face in the welcomed warming steam, greatly anticipating the first sip after a brief waft of the rich aroma leapt from the frothed tea.

I didn’t mind waiting for the moon to rise that night.